The Digital Panopticon: Mobilizing Artificial Intelligence for Surveillance and Policing

Author

Vic Passalent

Editor

Rebecca Dragusin

Publications Lead

Artjom Gavryshev

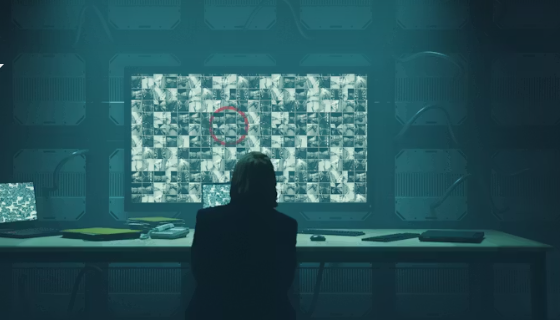

Michel Foucault’s analysis of the panopticon, detailed in Discipline and Punish (1975), uses Jeremy Bentham’s 18th-century prison design as a metaphor for modern disciplinary societies. Foucault utilized the panopticon to illustrate how modern society transitioned from punitive, violent, and public power to invisible, continuous, and normalizing disciplinary power. The digital panopticon takes the metaphor even further, becoming an “all-seeing digital system of social control, patrolled by precognition algorithms that identify potential dissenters in real time.” Novel technologies surveil and control, but the power is in prediction.

The concept of a total surveillance state, which utilizes invasive online monitoring, censorship, and oppressive policing systems, to control the civilian population, is an Orwellian nightmare. But has the nightmare collided with reality? This report uses the case of Clearview AI in Canada to investigate the use of biometric data in the building of digital identification technology and its mobilization for surveillance and policing.

Biometric Data Defined

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) defines biometrics as “the quantification of human characteristics into measurable terms.” The process of quantification is categorized into two main types of information: physiological biometrics, such as fingerprints, iris patterns, facial geometry, and DNA; or behavioural biometrics that involve distinctive characteristics of individuals’ movements or gestures, such as keystroke patterns, gait, voice, or eye movement.

Biometrics collected for the purpose of training digital identification (ID) software use machine learning to distinguish one individual from another. Training often requires vast repositories of high-quality data. In the process of identification, facial or voice recognition software, iris scanning, and fingerprint scanning mobilize this data for the purposes of identifying an individual.

Conversely, biometric identification is an imperfect technology prone to bias. Although NIST reports that facial recognition technology (FRT) is 99.5% accurate in controlled settings, error rates climb to 9.3% under sub-optimal conditions. Furthermore, FRT classifiers perform poorly on racialized and female faces – on darker female faces error rates climb to 20.8% to 34.7%. This unreliability can have life-changing consequences. St. Louis resident Christopher Gatlin spent over two years clearing his name following his arrest and imprisonment after facial recognition software connected his name to a violent crime. For racialized communities already facing disproportionate police interactions, FRT exacerbates the systemic problem of racial profiling in policing.

Biometrics in Policing: Clearview AI Case Study

The Clearview AI controversy was a litmus test for civil responses to AI technologies in policing. On 10 June 2020, a CBC article documented the covert use of biometric data and facial recognition technology by the RCMP as well as the Toronto, Halton, and Peel police services. This was followed up in February 2021 by a joint investigation conducted by the OPC and three provincial privacy authorities. The investigation determined that Clearview AI had violated federal and provincial privacy laws by scraping over 3 billion images from the internet without consent and creating a facial recognition database.

Canadian law enforcement, including the RCMP, had used Clearview's services before the company ceased operations in Canada in July 2020. Although the OPC stipulates that police agencies may seek and obtain judicial authorization to collect and use facial biometrics, legal authority must also negotiate Charter protections such as reasonable expectations to privacy. The commissioners characterized Clearview's practices as "mass surveillance," noting the company scraped highly sensitive biometric information from Canadians, including children, the vast majority of whom will never be implicated in any crime.

Despite stopping its Canadian operations, Clearview initially refused to delete images already collected, prompting provincial commissioners in Alberta, BC, and Quebec to issue formal orders in December 2021. A separate OPC investigation concluded in June 2021 that the RCMP's use of Clearview violated the Privacy Act, though the RCMP disputed this finding. Subsequent court challenges by Clearview saw mixed results: in 2025, Alberta's Court of King's Bench ruled that consent exceptions for “publicly available” personal information under AB PIPA were unconstitutionally narrow, while BC's Supreme Court in 2024 upheld that provincial privacy laws apply to biometric data scraped from social media, even from public profiles.

Although government institutions and civil society organizations, like the #Right2YourFace coalition, condemned Clearview AI’s actions as well as the lag in federal and provincial regulatory responses, police forces avoided severe scrutiny. While there are established use cases for digital ID software – i.e., border control, where FRT is utilized to screen incoming visitors to the country – it is another to turn those technologies against innocent Canadian citizens en masse. As this becomes an emerging use case for artificial intelligence, current offerings do not have the appropriate consent and security protocols built-in to ensure that privacy violations, such as data scraping to train FRT algorithms, are minimized and that surveillance cannot be conducted on a mass scale. Likewise, the Canadian government does not have the necessary legal mechanisms in place to reduce the risk of bias or false identification and to protect the privacy rights of Canadian citizens. Civilian police forces have an obligation to protect their communities – investing in digital ID software as a panoptic surveillance tool does not serve this purpose.

Recommendations

Overcoming the challenges will require the following recommendations:

1. Amending and modernizing outdated privacy legislation.

Canada’s current private sector privacy legislation, PIPEDA, does not provide specific protections for the highly sensitive biometric data that fuels facial recognition technology. FRT systems developed by the private sector for use by national security agencies are exempt, and biometric data is not explicitly identified as sensitive information within the legislation. Canada urgently needs legislation that classifies biometric data as highly sensitive, uniquely identifying material. Amendments to PIPEDA are overdue, but novel legislation must also outline consent protocols, define acceptable use cases, establish appropriate penalties, and standardize acceptable accuracy measurements for private sector software utilized by national security systems. Reclassification of biometrics, and higher standards for FRT systems, clarifies vagaries, encourages compliance, and generates accountability mechanisms to penalize private sector actors or police organizations that do not comply.

2. Strengthening enforcement capabilities for the OPC, including the ability to mandate regulatory government audits or apply significant monetary penalties for privacy violations.

Currently, institutions like the OPC, and its provincial counterparts, provide guidelines for the use of biometric data by law enforcement, the private sector, and the public sector. However, these government bodies are not equipped with the power to apply monetary penalties or enforcement mechanisms (such as mandatory government audits) to police or the private sector. Therefore, there is no enforcement mechanism to discourage inappropriate or exploitative use of biometrics for mass surveillance purposes. A stronger regulatory framework outlining discretionary powers for the OPC will hold AI firms and police accountable.

3. Implement a moratorium on the use of biometric data in policing for the purposes of surveillance.

The Government of Canada must impose a moratorium on the use of facial recognition technology, and biometric data more broadly, by federal, provincial, and municipal services for the purpose of civil policing. The collection of biometric data from civilians is substantially different from a criminal database of convicted offenders. As in the case of Christopher Gatlin, biometrics and FRT produce outcomes where innocent civilians are falsely imprisoned due to the built-in bias and the unreliability of the technology. However, where security risks have been acutely identified (i.e., land borders, airport entry and exit points), and close-circuit camera coverage is more robust, there is an established use case.